THE

CREATION OF SAN FRANCISCO's

NBC RADIO CITY MURAL

By John Schneider, W9FGH

www.theradiohistorian.org

Copyright 2018 -

John F. Schneider & Associates, LLC

(Click on photos to enlarge)

An architect’s rendering of the NBC studio building, showing the preliminary image of a different mural, 1940.

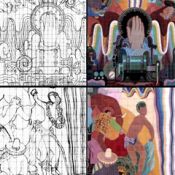

Fitzgerald's original concept sketch

of his NBC mural

Fitzgerald is seen working on his oil painting rendition of the mural, matching each individual color to the glazed tile samples laid out on the table in front of him

Another view of Fitzgerald working on his oil painting.

Fitzgerald is seen

speaking at the dedication ceremony of the Radio City mural, on

January 17,

1942

The grand unveiling

of the mural on

January 17, 1942.

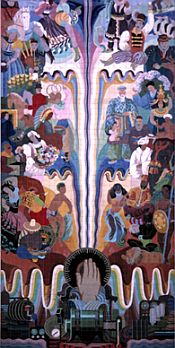

Fitzgerald’s completed mural, 1942.

The finished mural, in full color, as seen today.

Fitzgerald's signature on the NBC mural

CREATING OF A WORK OF ART:

There is a fascinating story

associated with the ceramic

tile mural that graces the façade of the NBC Radio City Building in San

Francisco (now known as the 420 Taylor Building).

The author was fortunate to acquire the files

of the mural’s designer, architect Gerald F. Fitzgerald, which revealed

a

number of heretofore little-known details.

In 1941, when the building was

first being designed and constructed,

it was decided that an important feature of the façade would be an

imposing

mural set into the 80 foot pylon that was to rise above the entrance

marquee. But the

subject of the mural

was yet to be decided. Early

architectural drawings of the building depict the large figure of a

standing

woman with nondescript figures scattered around her.

In reality, this was just a conceptual

drawing to the fill the space, and the true nature of the mural was yet

unknown.

As construction progressed, a

committee was formed to decide

on the artwork and implementation of the mural.

It consisted of Albert Roller, the building’s chief

architect; Roller’s

architural designer, Gerald. F.

Fitzgerald; Al

Nelson, NBC assistant

vice president in charge of San Francisco operations; O. B. Hanson,

NBC’s vice

president of engineering; William

A.

Clark, the manager of NBC Technical Services; and Curtis Peck, chief

engineer

of NBC’s San Francisco operations. Scores

of ideas were discussed by the committee, but they could not come to an

agreement. Outside

artists and sculptors

were invited to submit suggestions, and yet weeks passed without a

decision. Finally,

Fitzgerald proposed a

mural that would portray radio broadcasting serving all the peoples of

the

world. He submitted

a rough sketch, and

it won unanimous approval by the design committee.

Fitzgerald was then put in charge of the

design and execution of the mural project.

His design depicts the story of

radio broadcasting as a

means of mass communication reaching all the peoples of the earth. The mechanics of

broadcasting are represented

at the bottom of the work, with condensers, a dynamo, stop watch,

insulators,

transmitter tubes, a thermometer, wiring symbols, and an RCA

microphone. Immediately

above that, a large human hand adjusts

a radio dial creating radio waves that extend upwards towards the very

top of

the mural. On each

side of the wave, more

than 50 characters are depicted. They

represent

populations from the South Seas to the Arctic, from the Orient to the

West, and

from the tropics to the poles. The Oriental peoples are seen on the

right, and western

populations are at left; the

people of

the tropics are at the bottom, and the Arctic regions are represented

at top. Individual

characters portrayed include Africans

with a lion, Asians with a Chinese mandarin, and the peoples of Spain,

Mexico

and South America. There

are an American

cowboy and Indian, a Canadian Mountie, and an English riding gentleman. Balkans, Scandinavians, a

Cossack are

represented; an

Eskimo is seen with a polar

bear, penguins, a totem pole and an igloo. Also depicted are a

bullfighter, a

head hunter, an artist, reindeer, dancing girls and a Scottish piper.

The committee then turned to

the details of the physical

construction of the mural . It

would be

16 feet wide and 40 feet high. The

façade of the concrete wall that would surround the mural would be

textured

with horizontal fluting; the shadows caused by the fluting were

designed to

darken the surface to the eye, thus creating a darker grey background

for the

mural.

Most murals of the early 20th

century were

painted on indoor walls, allowing the portrayal of extremely fine

details. But

outdoor murals typically were constructed

of small single-colored colored tiles that were assembled to create an

image. This

technique would not display

the level of finer detail of the individual characters that were

depicted in

Fitzgerald’s drawing. In

a search for a

method to display such detail in an outdoor work, the committee’s

attention was

drawn to the artistry of the ceramics manufacturer Gladding, McBean

& Co.,

in Glendale, California, and it soon met with Leon G. Levy, the

company’s vice

president. Levy

offered a concept that

had never been attempted before – the mural could be built from

individual six-inch-square

glazed tiles, and each tile would be hand colored with small segments

of the

total image. The

square tiles would be

set end-to-end, with no mortar separating them, to form a continuous,

detailed

image. Unlike other

methods, the brilliant

colors of these glazed tiles would never fade with time.

At the ceramics shop, work

began on making the 2,560

individual six-inch tiles that would be used for the project. The materials for each

tile were mixed from a

finely-ground combination of talc, silica, rock and clay. They were pre-cut to their

precise size, with

an allowance for shrinkage during firing, so that each finished tile

would be

accurate in size within 1/13,000th of an inch. The tiles were fired as

they moved for 2-1/2

hours through a 108-foot-long kiln tunnel heated to 2,150 degrees F. After firing, graphic

artist Marcello Maruffo

drew the lines of each image segment onto the raw tiles, and then a

crew of

female artisan workers flowed the metallic oxide colors onto each tile

from

syringes. Once the

tiles dried, the

glaze was applied and they then made a second trip through the kiln

tunnel –

this time for 16 hours at 2,000 degrees F.

Finally, a grand unveiling

ceremony was held on January 17,

1942. The one-hour

event took place in

front of a live audience on a temporary outdoor stage constructed at

the front

of the NBC building. The

second half of

the event was broadcast live over NBC’s station KPO.

The dedicatory program consisted of dignitary

speeches, music by the NBC orchestra and the Symphonic Seven jazz band,

songs

by several local vocalists, and an original tone poem by Forrest Barnes. Finally, Fitzgerald

himself was introduced to

make a short statement:

Thank

you John Galbraith. It

is a new

experience for me as an architect to be called an artist. In accepting this very

high honor which you

bestow on me, I should like to acknowledge the enthusiastic support

given me by

Mr. Albert Roller and the friendly criticism of Mr. Nelson Poole, the

skillful

workmanship of the Gladding, McBean Company in Glendale where these

tiles were

manufactured, and the Sunset Tile Company of San Francisco who set them

in

place. In

creating this mural, I have

attempted to portray the unlimited scope of radio broadcasting, and its

service

to all the peoples of the world. Thank

you.

The grand finale to the program

was the dropping of the

canvas covering, and the creator and audience alike were treated to its

first

view of Fitzgerald’s masterpiece mural, which continues to grace the

streets of

San Francisco to this day.

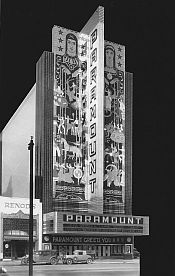

FOOTNOTE:

Very little

is known about the artist, Gerald J. Fitzgerald.

It was reported at the time that he had studied

architecture at the University of California in Berkeley, and then

worked for

the architectural firm Miller & Pflueger during the design of

stately the

Paramount Theatre building in Oakland.

According

to David Boysel, curator of the Paramount Theatre, Fitzgerald designed

the two

large gilded murals that still grace the front of that imposing

structure, and was

also responsible for the designs of the grand lobby and auditorium

ceiling. Apparently,

he also served as an architectural

consultant during the construction of the Bay Bridge.

Fitzgerald left the employment of Miller

& Pflueger sometime in the late 1930s, and was working for

Albert Roller at

the time of the NBC building project.

However,

nothing is known about Fitzgerald’s work or his life after he completed

the NBC

mural. His legacy

survives in the form

of the two great building murals he designed, which fortunately still

survive

today. If one looks

closely at the Radio

City mural, they can see Fitzgerald’s signature in the tiles at the

lower

right-hand corner.

www.theradiohistorian.org

John F. Schneider & Associates, LLC

Copyright, 2018