|

www.theradiohistorian.org

Copyright

2025 - John F. Schneider

& Associates, LLC

[Return

to Home Page]

(Click

on photos to enlarge)

Evangeline Adams was an astrologer who broadcast

nationwide over the CBS network in 1930.

KELW’s “Daddy Rango” and his assistant posed

inside his traveling radio bus, overflowing with letters from his

listeners.

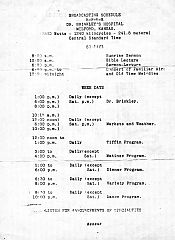

Daddy Rango program ad

Ralph Richards

John R. Brinkley

Cover of an XER promotional booklet, 1931

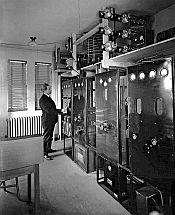

XER's original 150 kW transmitter

Norman Baker and KTNT's transmitter

Members of the Federal Radio Commission, formed

by Congress in 1927.

|

|

RADIO - A NEW OPPORTUNITIES FOR SCAM ARTISTS:

In 1922, radio broadcasting exploded in the United States

virtually overnight. This new form of

entertainment and communication burst upon the scene and was quickly embraced

by millions of Americans. Its sudden growth

was comparable to the overnight adoption of the Internet in our lifetimes. And just like the Internet, radio in its

early years proved to be fertile ground for hundreds of unscrupulous

characters, crooks and shysters. It took

the determined action of the nascent Federal Radio Commission (and later on,

the Mexican government) to clean up the airwaves and clear the way for an

honorable and successful broadcasting industry.

Here are a few stories of some of the scoundrels that plied the airwaves

of the 1920’s.

ASTROLOGISTS, FORTUNE TELLERS, NUMEROLOGISTS AND MIND READERS

At the start of the Great Depression, astrology was experiencing

a sudden surge in popularity. Once limited

to the fringes of society, the practice suddenly found mainstream popularity as

people, disillusioned by society’s downturn, started searching for alternative explanations

for life's uncertainties. The boom started

when newspapers began publishing daily horoscopes, offering vague predictions and

advice for each zodiac sign. It was only

a matter of time before radio would join the bandwagon.

It began innocently enough.

Leona Lamar was probably radio’s first spiritualist. She broadcast for a few weeks over Boston’s WNAC

in 1924, answering mailed-in questions. The following year she was heard on WHN in New

York. Then, starting in 1930, New York astrologer

Evangeline Adams gained a large national following, being heard three times weekly

over the CBS network. She offered her personalized

readings and predictions to listeners who wrote in by the thousands. At the height of her popularity, Adams reportedly received 4,000 reading requests

a day and employed dozens of assistants to open and answer her mail.

Small-time radio stations quickly took notice of Davis’s success

and began looking for the own broadcast astrologers. In these years before the acceptance of radio

advertising, any program that generated revenue was a draw. This unfortunately led to the hiring of many charlatans,

who saw radio astrology as a way to make a quick buck by fleecing their listeners. For decades, vaudeville theatre had presented

a wide assortment of fortune tellers, psychics, spiritualists and mind-readers. They were frequently presented in exotic and mysterious

attire, such as Oriental style robes and turbans and using props like crystal balls. It was up to their audience whether or not to

believe the performances were genuine, but the performers’ primary goal was clearly

to separate gullible people from their cash.

Before long, many of these con artists realized that radio would give them

exposure to a much wider audience, with a resulting greater financial return. Soon, astrologers and fortune tellers began appearing

on the airwaves across the country. Listeners

would mail in their questions and hear them answered over the radio. Typically, it was necessary to enclose a dollar

bill with each request. Thousands of such

letters would generate thousands of dollars in weekly revenue.

These programs would usually begin with a soft chime or the hypnotic

music of the “Song of India”, followed by the soothing voice of the swami, sometimes

cloaked in a faked foreign accent -- you could almost detect the scent of incense

coming from your radio speaker. These disembodied

voices offered to foretell a listener’s future , provide astrologic guidance on

critical decision-making, or resolve their doubts on issues of romance or finance.

Sometimes, local law enforcement would take note of this questionable

use of the radio airwaves. Wilbert W. Holley,

a practitioner of the art of radio clairvoyance in Rochester, NY, found his fortune-teller

broadcasts over WHEC being investigated by the local police after they received

reports that his misleading predictions had caused domestic strife. His strategy included the sale of astrological

charts and guides to romance, marriage and business success. He reportedly received from 500 to 700 letters

daily. Meanwhile in Cincinnati, fortune-teller

Dr. Allah Regeh suddenly disappeared from the WKRC airwaves one night. It turned out that he had been arrested by the

local police for practicing astrology without a license. Regeh’s defense to the charges was that such a

license did not exist. He was nonetheless

fined $100 and given a suspended sentence.

He left Cincinnati and headed to New York City where he undoubtedly continued

his radio activities on another station.

Rev. Ethel Duncan was another noted astrologer, billing herself

as the “Good Samaritan”. She was the founder

and pastor of the obscure First Church of the Apostles in Los Angeles, and broadcast

her daily “Question and Answer Lady” program over KNX from 1930 to 1932. Letters

poured into her home office seeking personal advice or help with financial problems. The Hollywood Daily Citizen reported that

Duncan once received over eleven thousand letters in one week! She often resolved the most desperate cases

by pleading to her audience for assistance.

The donations of money or goods would then pour in to help the beleaguered

souls –all provided by the generosity of her listeners with few contributions from

her own wallet. She was once denied a location

in Los Angeles for her Good Samaritan Relief Station when she refused to allow the

city to review the books of her organization. “Charity does not mix with red tape”, she explained.

Albert Cooley, calling himself “Daddy Rango”, the “common sense

psychologist”, was another Los Angeles radio

mentalist and a purveyor of patent medicines.

He broadcast over KELW Burbank and KGER Long Beach from 1928 to 1933, and

reportedly received over 300,000 letters during that time. Like the Rev. Duncan, his calls for donations

from his listeners drew generous responses at little expense to himself. Additionally, he promoted the mail order sales

of several patent medicine products, such as “Daddy Rango’s Laxative Herb Tablets”,

which were said to cure headaches, dizzy spells, neuritis, and liver and kidney

troubles. After being kicked off the air

in the U.S., Rango broadcast from XEMO in Mexico until he was banned there as well

by government officials in 1935. The Federal

Trade Commission finally shut his mail order business down in 1936.

One particularly egregious

radio “spook” was Ralph Richards, who had been traveling the country doing

magic and mentalist shows before discovering radio. In February, 1932, he began broadcasting twice

daily over WQAM in Miami, billing himself as Dr. Ralph Richards, a psychologist

and mental scientist who had studied astrology in India, Persia and Burma. His strong voice and convincing patter attracted

thousands of listeners to his programs. His

“Question Box” reportedly drew 500 letters each day, and he would answer these personal

queries by consulting astrological charts and the star signs of the writers. After WQAM, he broadcast over WWJ in Detroit for

a short time, moving on to WWNC in Ashville, NC, then to WBAX in Wilkes-Barre and

WLBW in Oil City, PA. Station managers reported

that the amount of mail received “exceeded anything we have ever witnessed”. In September of 1933, he appeared over KFEQ in

St. Joseph, MO, as “Dr. Price, the world-famous spiritual psychologist”, and then

moved on to KSO in Des Moines as “Dr. Raymond Vance”. He later appeared on KFAB in Omaha, WHDH and WNAC

in Boston, and WIOD in Miami. His pattern

at each of these stations was the same – he would book an engagement on a local

radio station and broadcast daily for two or three weeks, collect the dollar bills

from thousands of letters, and then skip town without ever answering any of the

correspondence.

JOHN BRINKLEY’S GOAT GLAND HOSPITAL

Much has been

written about John Brinkley, radio’s famous “goat gland doctor”. The flamboyant but unscrupulous “Doctor” John

Romulus Brinkley (who did not possess a valid medical degree) operated the Brinkley

Hospital in Milford, Kansas, where his signature procedure was the grafting of goat

testicles into the genitalia of middle-aged men who yearned to rejuvenate their

youthful sex lives. In those days before

Viagra, this was very big business – albeit totally fraudulent and without any medical

basis– and Brinkley had a corner on the market, amassing a substantial personal

fortune in the process. In 1923, Brinkley

built a radio station to promote his hospital – KFKB, “Kansas First, Kansas Best”. He used the public airwaves to advertise his goat-gland

procedure throughout the Midwest and also dispensed medical advice, prescribing

his own patent medicines over the air through a program called the “Medical Question

Box”.

Brinkley’s lifelong

adversary was Dr. Morris Fishbein, editor of the Journal of the American Medical

Association, who had built a career out of exposing medical fraud. On several occasions, Fishbein had publicly exposed

Brinkley as a “quack” and made it his personal goal to close down his operation. In 1930, Fishbein complained to the Federal Radio

Commission that Brinkley was using KFKB to promote his medical fraud. A formal hearing followed in Washington which

resulted in the cancellation of Brinkley’s broadcasting license.

Never a person

to ride quietly into the sunset, Brinkley searched for a scheme that would allow

him to sidestep those two powerful organizations and keep his lucrative radio and

medical businesses. During a 1931 vacation

in Mexico, he found his answer -- he was able to convince Mexican radio authorities

to give him a license for a new and powerful radio station – the first of the infamous

Mexican “border blasters”.

The construction

of the continent’s most powerful radio station began in Villa Acuña, Coahuila, in

the summer of 1931. XER’s towers were just

a stone’s throw from the Rio Grande River and designed to aim their signal to

the North. On the opposite side of the river

was the city of Del Rio, Texas, whose city fathers welcomed the economic boost the

station would bring during the depths of the depression. Further, Texas authorities were willing to license

Brinkley to practice medicine and open a new hospital in Del Rio. In October of 1931, XER burst onto the airwaves

with 150,000 watts – later boosted to an astounding 525,000 watts! Its powerful nighttime-only signal blanketed the

United States at 735 kHz, overpowering any other radio station that was nearby

in frequency.

Brinkley

promoted his goat-gland surgeries and patent medicines over XER, now free from

the reach of American authorities. But

he didn’t count on trouble from the Mexican Health Department, which ordered

the station shut down in 1933. After

considerable finagling with the Mexican authorities, he returned to the air in

1935 under the call sign XERA, this time on 840 kHz.

At XERA,

anyone could broadcast if they could pay the hourly fee. Soon, the schedule was filled with

astrologists, numerologists, fortune tellers, mining stock swindles and radio

lotteries - and the money poured in through the mails from American listeners

who happily paid for their services. The

typical fee was a dollar, and there were so many one-dollar envelopes flowing

into the post office that the city gained the nickname of “Dollar Rio”.

The end

finally came in 1941, when Mexican president Manuel Ávila Camacho ordered the

expropriation of XERA because of “undue influence by foreign elements”, and

because it had transmitted “news broadcasts unsuitable for the new world”. The huge XERA transmitter was disassembled in

July and taken to Mexico City, where it was installed at XEX.

In March of 1939, a Del Rio court charged Brinkley with

medical fraud. The judgement opened the floodgates

to an estimated $3 million in malpractice lawsuits from injured former patients

and the families of deceased patients of his goat gland surgery. Brinkley finally declared bankruptcy in January

of 1941, and suffered a fatal heart attack the following year.

Brinkley’s initial success inspired a number of others to

open another half dozen “border blaster” stations, and they continued to be

heard off and on into the 1960’s.

NORMAN BAKER

Norman Baker was the country’s second most illicit medical fraudster. In 1925, Baker opened his radio station on a hilltop

overlooking Muscatine, Iowa, and the Mississippi River. And the KTNT call sign, said to stand for “Know

the Naked Truth”, aptly described an “explosive” operation. He started out with a modest 500 watts but in

1928 was approved for a power increase to 10,000 watts, giving him solid coverage

over a million Midwestern homes.

In 1928, Baker brought Harry Hoxey, a convicted medical swindler,

to Muscatine and began promoting Hoxey’s cancer cure elixir over the airwaves. By April of that year, Baker had opened the Baker

Institute in a converted roller rink and invited listeners from across the Midwest

to take his costly cancer cure. A single

injection of Baker’s magical potion was said to cure cancer and other diseases. (An analysis of the liquid was said to contain

corn silk, watermelon seed, clover, water, and carbolic acid.) Reportedly, the clinic was bringing in $100,000

monthly, which was mostly smuggled out in suitcases stuffed with cash. But it wasn’t long before Baker and Hoxey were

suing each other over division of the profits.

Baker’s broadcasts contained frequent attacks against the A.M.A.

-- the American Medical Association, which he called the “American Meatcutters Association”. He also levied frequent attacks against the Federal

Radio Commission, complaining of its inclination to assign the best frequencies

to the big corporate stations. He was railing

against the same powerful interests that had cost John Brinkley his license, and

they took note of it. In 1930, the AMA and

FRC banded together and hauled Baker into court, maintaining that his broadcasting

license should be revoked due to fraudulent usage of the airwaves. The Commission revoked KTNT’s license in June,

1931, stating:

“… the licensee of this station had

used the same to make bitter attacks upon various individuals, companies and associations

with whom he had personal differences; that

the station programs were composed largely of these attacks, and the direct selling

and price quoting of licensee’s merchandise, as well as the exploitation of the

medical theories and practices of licensee and his cancer hospital.”

At about this same time, the State of Iowa brought suit against

Baker for practicing medicine without a license. He took refuge in Mexico, but eventually returned

to serve a one-day jail sentence and pay a $50 fine. He then mounted a write-in campaign for governor

of Iowa, but garnered a mere 5,000 votes.

Following the example of XER’s John Brinkley, he applied to the

Mexican government and obtained a license for a border broadcasting station. In 1933, XENT in Nuevo Laredo became the second

“border blaster” station, operating with 150 kW from the banks of the Rio Grande

River. It blanketed the U.S. with promotions

for Baker’s cancer cure, which was now being administered at his new hospital locations

– first in Laredo and then at a larger facility in Eureka Springs, Arkansas.

The U.S. government was powerless to stop Baker’s Mexican broadcasts,

so it decided to deal with him in other ways.

In 1939, Baker was arrested for seven counts of mail fraud, resulting from

his soliciting patients for his hospital through the mail. He was convicted in 1940 and sentenced to four

years in Leavenworth Prison. XENT was sold

off to other owners and briefly operated until the Mexican government shut down

all its border blaster stations down in 1942.

Baker lived out his last years in Florida, where he died in 1958. His hospital in Eureka Springs still stands today,

now operating as the Crescent Hotel.

THE RADIO COMMISSION ACTS

In 1931, the broadcasters’ newsletter Heinl Report wrote:

“Scientific men are up in arms over

the flood of fake stuff that is pouring over the air daily, paid for by scheming

fortune-tellers, astrologers, quack weather profits and medical shysters, advertising

which has been banned by respectable newspapers as unethical for many years. The radio broadcasters appear to have no objection

to taking money from such doubtful sources, and the public harm that is being done

is incalculable.”

The flood of radio

astrologers and fortune tellers had already caught the attention of the Federal

Radio Commission. The FRC commissioners were

incensed about these programs, but the Radio Act of 1927 did not give them the authority

to censor program content ITSELF. Finally

in 1930 they determined to use a station’s license renewal as a mechanism for getting

such programs off the airwaves. They would

set a station’s renewal for a hearing, questioning whether its operation was “in

the public interest, convenience and necessity” as required by the Radio Act. An FRC press release was issued warning stations

about the issue:

“Upon frequent occasions, there has

been brought to the attention of the Commission complaints against radio stations

broadcasting fortune telling, lotteries, games of chance, gift enterprises, or similar

schemes offering prizes dependent in whole or part upon lot or chance. There exists a doubt that such broadcasts are

in the public interest. Complaints from a

substantial number of listeners against any broadcasting station presenting such

programs will result in the station’s application for renewal of license being set

for a hearing.”

The Federal Trade Commission also addressed the issue:

“Minor difficulty has been encountered

with astrologers and other star gazers, placing substantial responsibility for programs

of this nature on station managers. Broadcasters

are deficient when they permit ‘rank amateurs’ to pose as experts. …. Although

the big stations are not ‘entirely pure’, most persistent cases involve small, obscure

transmitters. “

The Radio Commission did indeed act on its threat. They seem to have focused on the West Coast, where the most egregious cases

perhaps existed.

In January, 1932,

the Commission received a letter of complaint from a listener of KFWI in San Francisco,

objecting to the broadcasts of an astrologer named Alburtus. He was on the air twice daily during the winter

of 1931 and spring of 1932, practicing fortune telling and answering letters over

the air, usually concerning the writer’s personal affairs. An astrological chart was offered for $1.00 each,

although answers on the air were not conditioned on the purchase of a chart. The

net returns on the sale of these charts were divided between the station and Alburtus.

At first, KFWI

did not seem to fully appreciate the implications of the complaints. It justified the broadcasts by saying they were

popular with the public and that other stations in the area were also carrying similar

programs. It’s likely that the broadcasts

were bringing in significant revenues that management was not eager to relinquish. Finally, in response to the Radio Commission’s

concerns, the KFWI manager wrote:

“The type of program in question was discontinued on April

6, 1932, and our good faith in the matter was further shown by the fact that radio

stations in this same area were broadcasting similar programs up to the time applicant

ceased the same, and even for a time beyond.

Among many others, KNX, Los Angeles, broadcasted this type of program long

after the Commissioner’s press release and as late as April 30, 1932; KQW San Jose as late as April 29, 1932; KTAB San Francisco and Oakland, to April 3, 1932,

to all of which broadcast exceptions have apparently not been taken.”

KFWI went on to explain the popularity of the program

and downplay the station’s earnings from it:

The Alburtus programs brought over 75,000 letters during their

existence. The average receipts were approximately

$1,000 a month gross. From this must be deducted

the expenses in connection therewith, including the proportion to Mr. Alburtus,

plus incidental expenses, which netted the station an average of less than $500

per month over a period of eight months, and these amounts came exclusively from

the sale of an astrological chart in pamphlet form at the rate of $1.00 each.

A hearing on the

KFWI case was held in Washington on May 6, 1932 by Examiner R. H. Hyde, who recommended

that the application for license renewal be denied, principally due to the astrology

broadcasts. He also emphasized that when

Alburtus responded to listeners’ letters over the airwaves, he was deliver point-to-point

messages to private individuals, which was not permitted for holders of a broadcast

license. After an expensive and lengthy

fight, KFWI’s license was ultimately renewed by the full Commission in August, acting

against the recommendations of the hearing examiner. But the financial difficulties the whole

process caused the station caused it to leave the air for good in 1933.

Other stations also came under the microscope of the Commission’s

investigations. KTAB in Oakland had its license

set for hearing because its broadcasts of the spiritualists “Zoro” and “Kobar”. KTM in Los Angeles found itself in trouble because

of its broadcasts of Zandra, KTM’s “Moslem Mystic”. He was described as an “eminent philosopher and

psychologist” who could “apply his science in solving everyday problems of individuals

and show them the way to prosperity and happiness.” Listeners were asked to send $1 for his Astrological

Revelations or Mystery Guide. KTM and Burbank’s

KELW were also cited for broadcasts by the operator of a cancer clinic who was not

licensed to practice medicine. The FRC hearing

examiner recommended that both station licenses be canceled, but they were

saved from extinction when both stations (who shared time on a single frequency)

were purchased by the newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst, KTM and KELW were combined to form a new full-time

station, KEHE (later KABC).

KFEQ in St. Joseph, MO, also got into trouble with the Radio

Commission because of its broadcasts of the aforementioned serial con artist Ralph

Richards, who broadcast under his own name for two months in 1933, and again in

February of 1934 as “Dr. Price”. The hearing

examiner wrote:

“…. He was represented not only as

an astrologer and psychologist, but as a doctor and scientist. He presumed to answer questions and to advise

concerning matters of business, domestic affairs, health, finance and investments,

love and marriage, and solicited sales of an astrological forecast offered together

with a general guide of the purchaser’s life with monthly charts for the current

and follow year at $1.00 a forecast.”

In the end, KFEQ’s license was renewed in 1935. In fact, none of the broadcasters investigated

by the Radio Commission for such broadcasts ever lost their license. But a lesson was quickly learned by the

country’s other broadcasters -- almost all of the radio astrologers, mind readers

and other assorted spooks had disappeared from America’s airwaves by 1933.

BACK TO THE BORDER BLASTERS:

Once the astrologers and fortune tellers found themselves banned

radio in the United States, many headed south of the Rio Grande, where Brinkley

and other border blaster station operators were keen to take them on for a share

of the earnings. For his part, Ralph Richards

took his scam to Mexico in 1937, where he broadcast from border stations XEPN and

XENT as “Dr. Richards, the Friendly Voice of the Heavens”, promoting his astrology

predictions as well as selling fraudulent oil leases. He was arrested for mail fraud in 1941, but skipped

bail and escaped to Texas where he continued to promote his oil lease scams. He was ultimately arrested again in 1942 and extradited

to Los Angeles where he was imprisoned for mail fraud.

The border blaster stations were home to innumerable astrologists

and fortune tellers during their short-lived reign (1931-1942). Gayle Norman II broadcast over XEPN in Piedras

Negras where he reportedly received over 2,000 letters a day. He claimed that he once received a plea for

help from a young man in Kentucky who worried that his mother’s home would be foreclosed

for non-payment of her $4,500 mortgage. He

responded that the funds to save her property would arrive in time from an unexpected

source. Lo and behold! The day before the mortgage was due, his mother

found precisely $4,500 in cash under a loose floorboard in the attic, where it had

been hidden by her grandfather!

Other border broadcasters included the astrologers Koran, Rood,

Marjah, and Brandon the Man of Destiny. The

Brinkley station XERA featured Rose Dawn, the "Patroness of the Sacred Order

of Maya" and her husband Koran, who conjured "wonders of mental magic"

and called down the ghosts of departed loved ones. Each day brought him five or more bags of mail,

each letter containing a dollar bill. An

office full of workers in Del Rio answered each letter with astrological charts

matching their birth dates. The

flamboyant Miss Dawn would pull up to her office each day in her pink LaSalle

and ask her staff the amount of the day’s “take”. Rose Dawn and Koran continued to fleece their

listeners until XERA was shut down in 1942.

POST SCRIPT:

It’s unlikely that there were any truly talented

fortune-tellers among the lot of radio’s spooks and pitchmen. If any of them was truly clairvoyant, it surely

wasn’t evident in their lives. Gayle Norman

lost a huge sum betting on horses at the Kentucky Derby, and Ethel Duncan was swindled

by a business partner. Their only

success came from the fleecing of their gullible radio listeners in an era when

the uneducated rural public was more naïve than today.

As with so many other

human activities, it took the implementation of public regulations to

establish order and respectability to the broadcast industry.

Now, if someone would just figure out how to do the same thing with the

Internet ....

This article

originally appeared in the June, 2025 issue of the Spectrum Monitor

REFERENCES:

- Border Radio by Gene Fowler & Bill Crawford; Texas

Monthly Press, 1987

- Radio Psychics: Mind Reading and Fortune Telling in American

Broadcasting by John Benedict Buescher; McFarland & Co., 2021

- Charlatan, by Pope Brock, Three Rivers Press, 2008

- “Norman Baker, a Life History”, by Ron Bopp

- “Norman Baker and the Naked Truth”, published by Roy Grennan, Florida State University Libraries

- “When Quackery on the Radio Was a Public Health Crisis”, by Jessica

Leigh Hester, 2018

- Annual Report of the Federal Radio Commission, 1931

- “Radio Doings” Magazine, 9/27/1931, 7/8/1931

- Val Verde County Historical Commission, https://www.vvchc.org/rose-dawn.html

- A podcast: “Evangeline

Adams and the Advent of Astrology in America”,

https://theastrologypodcast.com/2019/05/21/evangeline-adams-and-the-advent-of-astrology-in-america/

- “Evangeline Adams” by Karen Christino, https://karenchristino.com/evangeline-adams/

- Heinl Report 02/1931, 7/26/1935

- “Radio Doings”, 7/8/1931, pages 12-13: Daddy Rango

- “Radio World” magazine, 5/23/1931

A special "thank you" to Jim Hilliker for his help with the Daddy Rango portion of this article.

|