WARTIME VOICES:

EARLY SHORTWAVE BROADCASTING ON THE WEST COAST

By John Schneider, W9FGH

www.theradiohistorian.org

Copyright 2011 -

John F. Schneider & Associates, LLC

(Click on photos to enlarge)

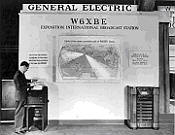

An overview of the General Electric shortwave exhibit at the Golden Gate International Exposition.

The huge transformers for the KWID transmitter arrive via rail. (Kevin Mostyn)

An interior view of the transmitter assembly. (Kevin Mostyn)

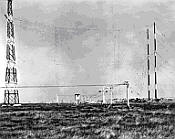

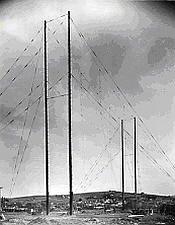

A view of the completed KWID and KWIX antenna farm, as it appeared in 1945.

The KWID and KWIX antennas are visible in this view, looking north from the Bay shore. The KSFO tower is visible at the far right. (San Francisco Public Library collection).

This 2020 photo shows the repurposed KGEI building, restored to its original appearance.

THE BEGINNINGS OF SHORTWAVE BROADCASTING ON THE WEST COAST

Shortwave radio broadcasting was still a novelty in the United States in the 1930’s. The shortwave frequencies had been in use since the mid 1920’s to relay programs from the East Coast to the West Coast, and to receive special event broadcasts from Europe. But now for the first time, manufacturers were selling radios that included a shortwave band, and the public was able to tune to these signals directly. The possibilities of reaching out to the entire world on the airwaves were just beginning to be explored, but no one had yet figured out exactly how to make use of it.

The first shortwave stations in the United States were all established by private interests. NBC, CBS, General Electric, Westinghouse and Crosley put some of the first signals on the air using transmitters of 10 kW and higher. In those early years, the shortwave bands were relatively empty and interference was low, so a 10 kW transmitter could be heard over great distances. At first NBC, and later CBS, built stations that targeted Latin America, principally rebroadcasting American English-language network programs. There was no defined business model for these stations — they were still exploring the possibility of developing future markets. General Electric, another company entering shortwave broadcasting was, apparently viewed it more as a market for the development of commercial shortwave transmitters. They operated W2XAD AND W2XAF in Schenectady, which mostly rebroadcast the programs of GE’s AM station, WGY.

But there was no shortwave broadcasting on the West Coast. The East Coast and Midwest signals could not be easily heard in the far flung countries of the Pacific. Starting in 1935, a California-born United States diplomat stationed in Shanghai named Addie Viola Smith decided to do something about this. She conducted an intense personal campaign to promote the construction of a West Coast shortwave radio station to serve the American expatriate community in the Pacific. That year, while serving her sixteenth year in China as a trade commissioner working for the Commerce Department, she began writing a series of letters to Washington urging the construction of a station. "I feel certain", she wrote, "that radio interests in China, especially in Shanghai, would welcome the institution of a special directionally beamed program from the United States." Shanghai, in particular, was the home to a community of 12,000 Americans, many of whom felt isolated by their great distance from their homeland. It would be a great gift and a way to send a wealth of knowledge across the sea to Americans who were trying to earn a salary abroad but couldn't find many reminders of home. Seing how great of a reward this would be, Smith kept her eye on the prize and started a continuous letter-writing campaign to Washington, in which she included logs of radio reception that showed how difficult it was to receive the American shortwave stations. In 1937, she complained of the expatriates’ inability to receive the broadcast of the second Roosevelt inauguration and the Metropolitan Opera broadcasts.

THE FIRST WEST COAST STATION

In the fall of 1937, Smith’s pleadings finally caught the ears of General Electric executives. GE had built pioneer AM station KGO in Oakland, California, but the station had been sold to NBC and so the company no longer had a West Coast radio presence. They decided it was time to re-enter the West Coast broadcast market, and they would do it by building a powerful new shortwave station. Since 1923, GE had been operating its powerful shortwave stations in Schenectady, New York (W2XAD AND W2XAF - later WGEO and WGEA). In its application to the FCC, the company quoted some of the statements that Viola Smith made in her letters as a justification for the license. The Commission, which had also received many pleadings from other sources, readily approved the application.

GE decided to tie their new station to 1939’s planned Golden Gate International Exposition. The big fair was going to be held on Treasure Island in the middle of San Francisco Bay to celebrate the completion of the area’s two big new bridges — the Bay Bridge and the Golden Gate Bridge. General Electric planned a big exhibit in the Palace of Electricity and Communications where it would showcase many of its advanced industrial and consumer products, including an all-glass house and new lighting technologies. This was also an excellent chance to demonstrate to the world the progress it had made in the development of shortwave transmitters and transmitter power tubes. The station would also serve as a worldwide goodwill vehicle for the fair by transmitting daily programs originating from the fairgrounds.

A brand new 20 kW G.E. transmitter incorporating the latest technological innovations was shipped to San Francisco and installed at the fair, and a compact studio and control room were built right next to the transmitter. A newly-designed directional antenna was hung between two poles atop the ferry building at the harbor entrance to the island. Its figure-8 coverage pattern created two narrow (30 degree) beams that would provide coverage to both Latin America and Asia.

The focus was on making the station into a public demonstration of the company’s industrial capabilities, but the actual programming for the station had never been seriously considered. Other than acquiring the rights to rebroadcast some NBC domestic network programs, there were no plans to assemble a program staff. E. T. "Buck" Harris, a GE public relations manager and former San Francisco newspaperman, dared to ask the question - what did the company plan to broadcast? The next thing he knew, he had the new title of Station Manager. He was instructed to put together four hours of daily programs for Latin America and three hours for Asia. Harris hired Norman Page to be the Chief English Language Announcer, and Carlos Benedetti as the Chief Spanish Announcer. Burt Scoals was the Chief Engineer.

The station was issued an experimental license with the call sign W6XBE, and it began broadcasting on the opening day of the fair, February 18, 1939, on 9,530 and 15,330 kHz. For the station’s official dedicatory program broadcast on March 4, GE and NBC executives joined local politicians and the foreign consuls of 19 countries to broadcast their greetings to the world. In the remaining months of 1939, more than 4 million fair attendees passed through the exhibit and marveled at the live broadcasts, which could be viewed through large plate glass windows. Only a railing separated them from the powerful operating transmitter.

In Shanghai, Viola Smith worked hard to promote the new station among the American community. She sent out press releases to the English and Chinese newspapers and local radio stations, and distributed copies of the station’s program schedule. When the first broadcasts began, she collected reception reports from friends around China and immediately passed word back to the station that it was being heard loud and clear.

Soon, news, music and public affairs programs stretched out daily over the oceans, to the delight of the local residents and American expatriates overseas. More importantly, W6XBE was the first American radio signal that could be heard across the Pacific, and so a regular audience quickly developed in the Philippines, China, Malaysia, Australia and other countries around the Pacific Rim. The station celebrated GE and the fair, and visiting dignitaries, entertainers and ordinary citizens alike were marched before the microphone to fill up the broadcast hours. The station offered a commemorative booklet about the fair to any listener who wrote in. The more than ten thousand letters received in response indicated that the station had developed a large and widespread audience around the world.

1939 was also the year that the FCC decided to end the "experimental" character of all shortwave licenses and issue permanent broadcasting licenses. However, while international stations had previously been allowed to operate with as little as 5 kW of transmitter power, the minimum power was now set at 50 kW. Furthermore, stations were required to install directional antennas to increase the effective power in the beam by a factor of ten or more. As a concession for the hefty expenditures needed to meet these new signal quality requirements, the FCC also relaxed its previous restrictions on advertising. Before that time, an international station could only broadcast advertising messages if they were already incorporated into domestic programs being relayed on shortwave. But now international stations could actively solicit or sell advertising, and messages from American multi-national companies like Firestone, Johnson Wax and the big tobacco companies were being heard for the first time.

Another result of the changing regulations was that the ham-style experimental call signs used by the shortwave stations would be replaced with conventional four-letter broadcast call signs. Thus it was that W6XBE became KGEI in September of 1939. For the live re-christening broadcast, GE hired some dancers from the Folies Bergère to change the big sign in front of the station.

The success of KGEI encouraged GE executives to keep the station on the air once the fair closed. NBC, which still had a close corporate relationship with its former partner GE, offered space for transmitting facilities next to the KPO AM (now KNBR) transmitting plant in the salt flats near Belmont. GE filed for a construction permit in December of 1940, and began building a new transmitter building and antennas. A reinforced-concrete building with 3-foot thick walls would house the transmitter, indicating the concerns about the possible future need of war security. A new 50 kW version of the first G.E. transmitter was delivered. Curtain antennas were built for the 19, 25 and 49 meter bands, aligned to cover Latin America at 126 degrees and Asia at 306 degrees. New KGEI studios were installed in the Fairmont Hotel on Nob Hill in San Francisco. After the fair closed in 1941, the station was soon back on the air from Belmont with an even better signal. In addition to its locally produced programs in English and other languages, many NBC programs from local stations KGO and KPO were also heard.

Despite its reliable international coverage, KGEI was only partially successful in meeting the needs of Americans living overseas, and was even less of a success in serving the Asian populations. While live American network programs were being relayed to Latin America each evening, the Asian programs needed to be sent out from 4:00 to 7:00 AM Pacific Time, when all the networks were silent. So KGEI instead broadcast pre-recorded music and transcription programs which were generally of lower quality. Eventually, some network programs were recorded and rebroadcast to the Pacific the next morning, but all the programs being heard were still in English. The result was that the station eventually succeeded in serving the American expatriate community overseas but it did very little to attract an Asian audience or build international goodwill.

It was even less successful when it came to news programs. GE had instructed Buck Harris to only broadcast "unbiased" news reports, so he contracted with the INS —International News Service — to install a teletype news service at the station, and staff announcers would deliver several "rip and read" news broadcasts each day with no additional commentary. However, the INS proved not to be entirely unbiased. The news agency was owned by the Hearst Newspaper chain, and so its news stories reflected the conservative slant of owner William Randolph Hearst. Hearst was an isolationist in those pre-war years, and firmly believed that the United States should stay out of the overseas wars in Europe and the Pacific, so he made certain that the INS news reports reflected his personal views. But the KGEI broadcasts were being heard across the Pacific by the Japanese, and they wrongly interpreted its news broadcasts as reflecting the official position of the United States government. As a result, they came to believe that a Japanese war of aggression in the Pacific would encounter little resistance from the United States. Further, the citizens of the Pacific Rim countries were hearing both the aggressive messages from Radio Tokyo and pacifist non-intervention messages from KGEI, and so they believed that the United States would not come to their defense in the event of a Japanese invasion.

To tell the truth, there were NO broadcasts of the United States government’s position being heard anywhere in the world at that time. The isolationist congress of the 1930’s, under strong pressure from the National Association of Broadcasters and other private broadcasting entities, had prohibited the U.S. government from conducting any direct broadcasting activities, either domestic or international. There was no way that the U.S. government could directly broadcast its official views and positions to the peoples and governments of the world.

Nevertheless, the Japanese apparently felt that the messages being heard in KGEI’s newscasts were biased against them, and so they started to create interference with its signals in May of 1939. They would generally leave the entertainment programs alone, but when the news broadcasts began Japanese stations XJI and XJZ would begin to transmit on adjacent channels, airing Japanese propaganda in English. Many listeners wrongly interpreted the Japanese programs as coming from San Francisco.

NEW GOVERNMENT AGENCIES

With war clouds on the horizon, the Federal Government began to take the first steps to form a centralized intelligence and propaganda agency. In the spring of 1940, President Roosevelt created a new agency called the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs (CIAA), headed by Nelson Rockefeller. The purpose of this new government agency was to strengthen ties among the nations in the Western Hemisphere. International radio was to be a part of this effort, and that responsibility was assigned to a new agency formed in July called the Coordinator of Information, or COI, headed by William "Wild Bill" Donovan. FDR’s speech writer, playwright Robert Sherwood, was named to head the Foreign Information Service, or FIS, which was a sub-agency of the COI. Its task was specifically to broadcast news and propaganda to foreign countries.

WILLIAM WINTER

The administrators of the new COI immediately started receiving reports from their contacts about the KGEI news broadcasts and the erroneous impression they were giving in the Pacific. And so suddenly the spotlights focused on a relatively unknown San Francisco news commentator named William Winter.

Winter was a news commentator at KSFO whose programs were being heard around the West Coast on a CBS network regional network starting in early 1941. In the style of the time, a news "commentator" was different than a news reporter. Winter did not report the news; rather he analyzed and explained the background of major stories, unraveling the complex politics behind many of the important issues of the day.

In September of that year, Winter received an unannounced visit from John Dumeresque, a British military officer who was in charge of the Malaya Broadcasting Commission in Singapore Dumeresque was one of the people focused on the problem of the KGEI newscasts, and he wanted the station to broadcast a more accurate position of the U.S. political position. He had contacts that reached high up into the American government — to Donovan and perhaps as far as FDR himself. Dumeresque told Winter he had made arrangements for him to broadcast two daily news commentaries over KGEI, and that his selection for the position had already been cleared with both CBS and GE as well as with the COI. The broadcasts would originate from KGEI’s Fairmont Hotel studios, and would be in addition to his daily broadcasts from KSFO in the Palace Hotel, for which he would be paid the nominal sum of $50 per month. He was not to be a spokesman for CBS, GE or any government. He was to explain the American system of government and the rights of the American people to express their own divergent views as guaranteed by the Constitution. It’s interesting to note that Dumeresque did not present this proposal as a request. By appealing to Winter’s sense of patriotism, he already knew that Winter would have to accept.

Because of the existing prohibitions against direct government broadcasting, the COI still could not directly control the content of the programs, but it did have the ability to "suggest" topics. The result was that a private teletype was installed under lock and key at KGEI for Winter’s exclusive use. He would come into the studio each morning to find the teletype closet full of "suggested" material. Everything he received was publicly available material — public opinion polls, newspaper editorials, magazine articles, books — all concerning U.S. policy and its position towards Asia. All material was marked "Winter: For you use if desired". It was understood that there would be no attribution to the COI as the source.

Winter’s program, called "American Views on the News", was first broadcast on Sunday, September 14, 1941. The fifteen-minute program was heard seven days a week at 6:45 AM Pacific Time. The KGEI broadcasts were also being picked up and relayed by Radio Malaya in Singapore. Additionally, Winter’s scripts were translated for broadcast in French, Dutch and Spanish.

THE OFFICE OF WAR INFORMATION (OWI)

Everything quickly changed after the December 7 Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, as the entire country shifted to wartime operations. The COI was reorganized and became the Office of Strategic Services or OSS — which would later become the CIA. The FIS became the Office of War Information, or OWI, and it was given the responsibility of controlling all public information about the war. CBS news commentator Elmer Davis was put in charge of the new agency. The OWI was instructed to take charge of all shortwave radio stations in the country. The peacetime rules prohibiting government origination of programs were not actually repealed, but they were now just ignored.

At the start of the war there were only ten shortwave stations in the entire country — all of them privately owned. NBC had WNBI and WRCA in Bound Brook, NJ; CBS owned WCBX and WCRC in Brentwood, NY; General Electric operated WGEA and WGEI in Schenectady and KGEI in San Francisco; Westinghouse ran WBOS in Boston; Crosley had WLWO in Cincinnati, and the Worldwide Broadcasting Foundation owned WRUL, Boston. Collectively these stations broadcast just 35 hours of programs a week — mostly relays of U.S. domestic network programs aimed at Latin America.

On December 15, 1941, just eight days after Pearl Harbor, the COI leased KGEI from General Electric, making it the first international station to be operated under direct government control. It would take another six weeks until the first government broadcasts from New York could be beamed towards Europe. KGEI’s new programs in English and Tagalog were targeting the Philippines, which was already under attack from the Japanese. The KGEI broadcasts were being received there and relayed on local AM frequencies. Programs in Japanese were later added, originating from the Press Building at the University of California.

The OWI established radio studios in New York to originate shortwave programs beamed to Europe beginning in February of 1942, leasing time on selected commercial shortwave stations. Radio actor John Houseman was named as the head of radio programming in New York. The BBC received the programs in Europe and relayed them to Germany.

Taking things one step further, on November 1, 1942, the OWI formally leased every shortwave station in the country for the creation of a "Voice From America". All station owners would continue to operate the transmitters, and the government would pay all expenses and providing the programming. (All the broadcasters except WRUL voluntarily agreed to this plan. The OWI ultimately seized the station by executive order.) All transmitter sites were off limits to the public and were guarded by the military as essential national infrastructure.

Back on the West Coast, KGEI’s powerful signal was still the only American voice in the Pacific, and the station had become a lifeline to foreign nationals as well as to American servicemen stationed in the Pacific. KGEI was now on the air twelve hours a day, broadcasting in Japanese, Chinese and Tagalog, and various Chinese and Filipino dialects. At the Fairmont Hotel studios, a superb staff of linguistic and cultural experts had been added to the original KGEI personnel, who had all now become government employees. Dr. Owen Lattimore, an expert on Asian culture, was named Director. Lee Raschal became the Managing News Editor. In addition to Winter, other announcers and commentators included Victor Lusinchi, Carlos Benedetti, Sydney Roger, Frank Johnstone, Pat O’Brien, Bill Conine, Bob Goodman and Merrill Phillips. Chinese and Japanese-American announcers were also on the staff, but their messages were not broadcast live — they were recorded and checked by multi-lingual censors before airing. Surprisingly though, most commentators were generally given the freedom to determine their own messages to be heard by foreign listeners. There were only three secrets that could not be broadcast: troop and ship movements, weather conditions or the location of the US president. Also, they were told to never let the Japanese know that the U.S. was hearing their shortwave broadcasts.

This sudden increase in human activity quickly overflowed the single KGEI studio in the Fairmont Hotel, and so in 1942 the OWI moved temporarily into a new studio complex that was being built for AM station KSFO in the basement of the Mark Hopkins Hotel. At the same time, NBC was moving out of its old West Coast studios at 111 Sutter Street and into its posh new "Radio City" building. The OWI converted the old NBC studios as its headquarters and moved in on January 1, 1944, turning the Mark Hopkins studios back over to KSFO.

MacARTHUR AND THE WAR IN THE PHILIPPINES

Just three days after Pearl Harbor, the Japanese bombed Manila and destroyed most of the American planes and ships stationed at its Philippine bases. Japanese ground forces landed on Luzon Island the same day and began to make their way towards Manila. Outnumbered and outgunned, the American forces under the command of General Douglas MacArthur, together with the Philippine forces, retreated to the Bataan Peninsula and later to the island of Corregidor.

From his provisional headquarters in Corregidor, MacArthur was listening to William Winter’s daily broadcasts over KGEI. MacArthur began to issue military communiqués, which were sent to San Francisco and broadcast back to the Pacific by Winter. What Winter didn’t know is that most of these 142 communiqués were just unrealistic promises of an impossible victory, intended to boost morale and disquiet the enemy, but the receiving audience in the Philippines was observing the true picture all around them and so the broadcasts were generally discredited.

Before abandoning Manila, the U.S. troops had disassembled a 1 kW transmitter belonging to station KZRH in Manila. It was carried to Bataan in pieces where it was reassembled and put back on the air as "Freedom Radio". The station operated from February to May of 1942, rebroadcasting KGEI programs to the Philippine people and U.S. troops.

In March of 1942, TIME Magazine described the operations of "Freedom Radio":

From California’s short-wave KGEI, the Army Signal Corps on Bataan now picks up and rebroadcasts some two hours of English programs every day. The stuff begins to come in on Bataan at 5 every afternoon (2 a.m. in San Francisco). It starts with a quarter-hour of straight news. Another quarter-hour is devoted to a roundup of editorial comments from the U.S. KGEI has added a daily half-hour of entertainment from fresh recordings: Monday, Jack Benny; Tuesday, Cavalcade of America; Wednesday, Bob Hope; Thursday, Eddie Cantor; Friday, Rudy Vallée. There is also news in Tagalog, and a discussion in English, Freedom for the Philippines.

Many news reports, letters and anecdotal stories from those years are filled with proof that KGEI’s broadcasts, as well as those of its sister shortwave stations after 1942, were important sources of comfort and hope to the people of the Pacific. These are just a few examples:

"He would tune in the short wave to KGEI in San Francisco and get the latest news of the South Pacific war. Consequently, we knew that the Americans were island hopping toward the Philippines."

"The news has been bad for the past few days. Apparently there was something to the rumor of the 9th; that the Japs had broken through our Bataan lines for we have been getting in reports, supposedly from K.G.E.I. which confirms this."

"San Francisco’s powerful short-wave stations KWID, KGEI and KWIX send a clear signal into all parts of the Orient. They are avidly followed by thousands of clandestine listeners in China, Java, Malaysia, the Philippines and French Indo-China."

April 1942: "KGEI had Mrs. Jonathan Wainwright broadcast a message of good cheer to "Skinny," accompanied by three wagging woofs from the General’s pet Labrador retriever."

Finally, as things in the Philippines began to look bleakest for the American and Philippine troops, General MacArthur was evacuated to Australia on March 12, 1942. Upon landing there, he made several "I will return" speeches in which he promised to return and recapture the Philippines one day. One of his speeches was relayed back to the Philippines over KGEI and was heard by thousands of people now living under Japanese occupation. Even though listening to the radio was punishable by death, many Filipinos defied the Japanese ban and hid radios in their homes which they would use to listen to KGEI.

Then, on April 9, 1942, 75,000 American and Filipino troops surrendered to the Japanese on Bataan. As POW’s, they would participate in the infamous Bataan Death March, one of the most heinous war crimes in the Pacific War.

In December of 1942, eager to be in the center of the action instead of on the sidelines, William Winter quit his jobs at KGEI and KSFO to join the war effort as a newspaper field correspondent. He went on to give a series of speaking engagements all around Australia before being stationed as a reporter in the Philippines. After the war, he received special commendation from the Philippine government in recognition of the importance of his KGEI broadcasts to the Philippine people during the difficult years of the war.

MR. DUMM GOES TO WASHINGTON

Even before Pearl Harbor, President Roosevelt was seeing the war clouds on the horizon and recognized that building more shortwave stations would be critical to America’s ability to communicate to the rest of the world. Roosevelt was already a big believer in the power of radio broadcasting, having successfully sold his "New Deal" plans for combating the 1930’s depression through his famous series of "fireside chat" broadcasts. He knew that the power of radio would be increasingly important during the upcoming war. But in the days before Pearl Harbor, he needed to find a way around the congressional restrictions on government broadcasting and the unwillingness of the Congress to fund international shortwave radio.

Thus it was that in August of 1941, an emergency meeting was called in Washington by William "Wild Bill" Donovan to plan the construction of new international shortwave stations. Government leaders, major broadcasters and equipment manufacturers were all invited. At that meeting, Donovan and Roosevelt laid out the situation and asked the participants to construct 32 new shortwave stations on the East and West coasts. The money was not available to fund the stations immediately, but FDR promised the broadcasters that he would reimburse them for their construction costs at a future date.

CBS and NBC quickly agreed to turn over all of their shortwave broadcast facilities to the COI. Powel Crosley, the owner of WLW in Cincinnati, also agreed to turn over his shortwave station WLWO to the COI and to build a new high-powered shortwave facility at Bethany, Ohio. San Francisco broadcaster Wesley I. Dumm, president of the Associated Broadcasters, Inc., (AM station KSFO), also agreed to build two new shortwave stations on the Pacific coast. Dumm described this meeting in an April, 1971, letter to this author:

Donovan, made an urgent appeal for me to come to Washington in August of 1941 for a meeting which was called to include President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Robert Sherwood and others for the purpose of organizing a "Voice of America", also attended by representatives of Great Britain and Australia.

During this meeting, not only was the first meeting organized for the birth of the "Voice of America", but also, President Roosevelt asked me if I would build two shortwave stations in San Francisco to serve the Far East. In his plea, he not only stated that NBC and CBS Networks had lost so much money broadcasting into South America with their shortwave stations but that they had refused to consider a station to be located in San Francisco in order to carry out his wishes.

President Roosevelt further informed me that he would reimburse me with emergency funds in his possession if he failed to find support for such an investment out of government funds.

Because of the jamming that KGEI was increasingly experiencing from the Japanese, the new San Francisco station was urgently needed for communications to the Pacific. General Electric agreed to take its big 100 kW transmitter out of service at WGEO in Schenectady and ship it to San Francisco. (A 50 kW transmitter was placed into service in Schenectady until a new transmitter could be built.) KSFO was in the middle of building a brand new transmitter building on Islais Creek in San Francisco, and the structure was hurriedly expanded to make room for a shortwave transmitter, adding an eleven-acre site west of the transmitter to contain the several curtain array antennas to be aimed at Alaska, the Far East, Australia and Latin America. Chief Engineer Royal V. Howard and his assistant by Al Towne (later the Chief Engineer of KSFO), planned and built the entire station in just eleven weeks at a cost of $250,000. The new station’s call sign was KWID (taken from the initials of its benefactor, Wesley I. Dumm). Test broadcasts commenced May 5, 1942, just five months after Pearl Harbor, and soon the station was broadcasting in ten languages up to twenty hours a day. With an Effective Radiated Power of several million Watts, the new KWID was said to be the most powerful shortwave station in the world.

AND STILL MORE TRANSMITTERS

As the war progressed, a veritable arsenal of shortwave transmitters was gradually being assembled around the country. In 1943, the government purchased 22 new GE and RCA transmitters, making a total of 36 frequencies aimed at Europe and the Pacific. KGEI received a new 100 kW transmitter, which went on the air as KGEX. A new 50 kW transmitter went to KWID and became KWIX. A Press Wireless transmitter was brought back to the U.S. from England and was installed in the McKay Wireless communications facility in Palo Alto to become KROJ. Additional stations added in 1945 were KROU and KROZ at McKay Wireless, and KRCA and KRCQ operated from the RCA point-to-point transmitter station in Bolinas. Further, NBC and CBS both finally agreed to build major shortwave complexes in California. CBS chose Delano as its site location and put stations KCBA, KCBF and KCBR went on the air in November, 1944. NBC opened its new facility in Dixon on December 27 and opened stations KNBA, KNBC, KNBI and KNBX. Another station, KRHO in Honolulu, had debuted just the day before. In all, seventeen West Coast stations were now rebroadcasting the OWI programs originating in San Francisco.

|

PACIFIC COAST SHORTWAVE OPERATIONS |

||

|

Station |

Frequency |

Broadcast Time |

|

(in kilocycles) |

(GCT) |

|

|

KROJ |

6,105 |

1005-1015 |

|

KWIX |

9,855 |

1005-1015 |

|

KGEI |

9,550 |

1005-1015 |

|

KROJ |

6,105 |

1045-1100 |

|

KGEI |

9,550 |

1045-1100 |

|

KGEI |

9,550 |

1405-1415 |

|

KGEI |

11,730 |

1705-1715 |

|

KROJ |

11,740 |

1705-1715 |

|

KROJ |

17,770 |

1930-1945 |

|

KROJ |

15,190 |

2045-2100 |

|

KROU |

17,780 |

2045-2100 |

|

KROU |

17,780 |

2145-2200 |

|

KGEX |

15,210 |

2145-2200 |

|

KROJ |

17,770 |

0015-0030 |

|

KROJ |

17,760 |

0305-0315 |

|

KGEX |

15,210 |

0305-0315 |

|

KROJ |

9,897 |

0415-0430 |

|

KWID |

11,870 |

0415-0430 |

|

KNBA |

13,050 |

0605-0615 |

|

KNBC |

15,150 |

0605-0615 |

A list of shortwave radio stations and frequencies aimed at the Pacific in 1945

Towards the end of the war, as the U.S. was increasingly successful in pushing the Japanese back to their homeland, the purpose of these stations gradually shifted from broadcasting war propaganda to entertaining the American troops stationed in the far-flung corners of the Pacific. Broadcasts of the World Series and college football games helped improve the morale of the many soldiers isolated so far from their homelands. Regular programs broadcast to the troops in 1944 had names like "Command Performance", "The Army Hour", "Your Marine Corps", "G.I. Jive" and "Hymns from Home".

On October 20, 1944, General MacArthur landed on Leyte Island, keeping his promise to the Philippine people. His new message, "I Have Returned", was broadcast from the deck of the Navy vessel "Nashville", picked up in San Francisco and relayed back to the country over KGEI, KWID and their sister stations.

POST-WAR INTERNATIONAL BROADCASTING

Finally, it was V-J Day — August 15, 1945. The war was over, most of the troops would soon come home, and the country could return to its peacetime activities. But — now what was to be done with this huge network of shortwave transmitters that the government had been leasing? It would eventually be transformed by the government into an international communications tool that would avoid a repetition of the mistakes of pre-war American isolationism.

On December 31, 1945, the Office of War Information was transformed into the Office of International Information and Cultural Affairs (OIC). The OIC, in turn, created the Voice of America (VOA) as its international broadcasting division.

On the West Coast, the VOA purchased the NBC and CBS sites in Delano and Dixon, and the two networks happily exited the business of shortwave broadcasting for the last time. The VOA also acquired the Crosley site in Bethany, Ohio. Those sites, with the addition of Greenville, NC, in the 1960’s, were the principal VOA shortwave sites for the next sixty years. The McKay and RCA stations quickly disappeared without fanfare. KGEI and KGEX continued to relay programs under lease to the VOA until 1948. The leases of KWID and KWIX continued until 1953, but were finally terminated by the government at the end of the Korean War. According to one account, the government finally ended those leases because of the inconvenient proximity of the transmitterse to the Hunter’s Point Naval Shipyard. The Navy had been required to off-load munitions from ships before they could approach the shipyard because of the risk of explosion caused by the RF radiation from the stations, and wanted to eliminate the expense and inconvenience of that process.

When the VOA leases finally ended, KSFO made the decision to close the stations. Wesley Dumm explained the reasoning in a 1971 letter:

The Associated Broadcasters, Inc., benefitted from the results of the NBC and CBS Networks and forfeited the operation of these stations when the operating appropriations ceased to be forthcoming, and decided to forfeit the licenses rather than to experience the same type of losses as were reported by NBC and CBS in their programming to South America.

Incidentally, the GAO refused to honor the costs advanced for the construction of KWID and KWIX, and President Roosevelt kept his word by giving me an order upon the Treasury Department, reimbursing me completely at the close of the war.

The two powerful stations left the air for the last time on June 30, 1953. The transmitters were sold to Far East Broadcasting Company who moved them to Manila. The antennas were dismantled and reportedly the wooden masts were sold for firewood.

The only private owner that decided to stay in the shortwave business was General Electric, who continued to operate KGEI as an international goodwill station for eight more years. Thus it was that "The Voice of Freedom" became "The Voice of Friendship". Its flagship program was the "KGEI University of the Air", hosted by Stanford University Professor Ronald Hilton. In 1956, GE shut down the station and sold it to a group of businessmen who tried unsuccessfully to operate it as a commercial venture until 1959. Finally, in 1960, the station was purchased by the Far East Broadcasting Company (FEBC), who in turn operated the station to broadcast religious and cultural programs to Latin America and the Far East for the next 35 years. Finally, facing increasing costs and declining listenership, FEBC decided to close KGEI. The station’s last broadcast was heard in July of 1994.

POST SCRIPT

Today, there are just a few remnants of the big West Coast shortwave facilities. The VOA site at Dixon was shut down in the 1990’s, and Delano went into mothball status in 2008. The RCA point-to-point transmitter site in Bolinas was closed in 1973 and the maritime station KPH, also located in Bolinas, is now maintained as an historic site by the National Park Service. The McKay site in Palo Alto has also been closed. The old KGEI studio/transmitter building is now a church. AM station KSFO still operates from the old KWID transmitter building at Islais Creek, but the former shortwave transmitter area is now a storage room and the antenna site is occupied by a rendering plant. Very few of the shortwave powerhouses of the 20th Century are still on the air now that satellites and the Internet provide cheaper means of worldwide communications, but our world today is defined in innumerable ways by the outcome of the Second World War. The pivotal role that shortwave broadcasting played in achieving that noble victory must not be forgotten.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Voice from America, a Broadcaster’s Diary, 1941-1944 by William Winter 1994, Anvil Publishing, Manila, the Philippines

On the Short Waves, 1923-1945: Broadcast Listening in the Pioneer Days of Radio by Jerome S. Berg, 1999, McFarland & Co. Publishers.

Broadcasting on the Short Waves, 1945 to Today by Jerome S. Berg, 2008, McFarland & Co. Publishers.

"Homeward Bound: Shortwave Broadcasting and American Mass Media in East Asia on the Eve of the Pacific War" by Michael A. Krysko. Pacific Historical Review, Vol. 74, No. 4 (Nov., 2005).

"The Voice of America: Origins and Recollections" by Dr. Walter R. Roberts

History of the AFRTS, "The First Fifty Years" — Chapter 2, Broadcast Beginnings — By Soldiers For Soldiers http://afrts.dodmedia.osd.mil/heritage/page.asp?pg=50-years

Wesley I. Dumm, letter to the author dated April, 1971.

Bruce Hunter, former KSFO and VOA engineer - letter to author dated April 28, 2011.

"International Broadcast Station KGEI: 1939-1994" by Jim R. Bowman, KGEI Manager 1963-77.

Radio to the Rescue – Lost in China! by Dr. Adrian M. Petersen http://www.radioheritage.net/Column3.asp

"A Voice Across the Pacific: KWID & KWIX" - by Dr. Adrian M. Peterson, Radio World, 4-23-08

"Voice of America: Palo Alto in California" by Dr. Adrian M. Peterson, Radio World, 3-1-07

"Last of VOA’s Wartime Transmitting Stations Goes Dark" by James E. O’Neal, Radio World, 3-01-08

"Radio X (For Experimental)", TIME Magazine, 8-28-39

"Radio and Asia", TIME Magazine, 12-29-41

"Radio: War of Propaganda", TIME Magazine, 5-11-42

Broadcasting Magazine, 10-13-41, 1-26-42, 2-8-43, 2-22-43, 1-17-44, 2-14-44, 10-13-47

The Radio Annual, 1939, 1940

"Battle of the Beams", Popular Mechanics, July 1941.

Brass Button Broadcasters: A Lighthearted Look at 50 Years of Military ...by Trent Christman.

"General Douglas

MacArthur - Fighter for Freedom" by Francis Trevelyn Miller,

http://hlrgazette.com/2010-articles/93-february-13-2010/846-hayes-bolithos-epilogue.html

Biography: JAMES D.

GAUTIER, JR. M/Sgt.

USAF (Ret.),

http://www.lindavdahl.com/Bio%20Pages/J.Gautier.bio.htm

The first radio broadcasts from ships, 1898 — 1950: The famous "I Have Returned" broadcast by General Douglas MacArthur in the Philippines http://www.offshore-radio.de/fleet/first5.htm#Nashville

THE STORY OF PHILIPPINE RADIO. http://images.i23i.multiply.multiplycontent.com/attachment/0/SikFKAoKCI4AABHzDZk1/Philippine%20Radio%20History%284%20in%20a%20page%29.pdf?key=cama52:journal:3&nmid=251466835

KGEI You-Tube video: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mmMoy_Gz7mc

NOTE: This article appeared in the Monitoring Times Magazine, July, 2011.