WGEO AND WGEA --

GENERAL ELECTRIC'S TWIN SHORTWAVE STATIONS

By John F. Schneider W9FGH

|

|

WGEO AND WGEA -- By John F. Schneider W9FGH |

|

www.theradiohistorian.org Copyright 2021 - John F. Schneider & Associates, LLC (Click on photos to enlarge)

This view shows the same room just two years later - January, 1941. The 100 kW WGEO transmitter is at right; the older 50 kW transmitter at left broadcast for WGEA. (Author's Collection).

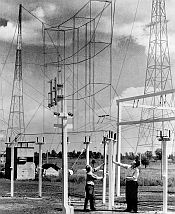

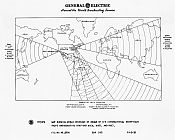

WGEO engineers are seen changing connections to the curtain antennas, September, 1940. Each vertical pole supports the transmission line for a different antenna, designed for a specific frequency and bearing. The line to the transmitter is attached by means of a long, insulated pole. (Author's Collection).  Another view of the antenna switching bay, November, 1941. The antennas are labeled “9550/9530 KC Europe/London”, “9550/9530 KC Latin America Buenos Aires”, “9550/9530 KC Latin America Rio”, and 15,330 Europe/London”. (Museum of Innovation and Science, Schenectady)  This view shows the 9,530 kHz curtain antenna of WGEO, targeting South America, November, 1941. (Museum of Innovation and Science, Schenectady)  This map, dated November, 1939, shows the directional antenna beams of WGEO, WGEA and KGEI. (Museum of Innovation and Science, Schenectady)  This was the W2XAF radio studio in May of 1939, broadcasting a program in Spanish. Announcer José Flores is seated at microphone; Prof. Vicente Tovar IS standing; and Aida Trennert is at the piano. (Museum of Innovation and Science, Schenectady)  This is the opposite view through the control room window, looking back into the W2XAF studio. (Museum of Innovation and Science, Schenectady)  In May of 1935, W2XAF broadcast a unique inter-continental bridge game by radio. C. H. Lang, G.E. publicity manager (L) and John Lockton, G.E.’s assistant treasurer (R) were the north and west players in Schenectady. They played against a team of players located in Barranquilla, Colombia. The north and west bids were transmitted over W2XAF on 9,530 kHz; the east and south bids were returned over HJ1ABB on 6,440 kHz. The bridge hands were shuffled and dealt from VK2ME in Sydney, Australia. (Author's Collection).  Here is N. Subramaniam of Bombay, India (today called Mumbai), transmits a program in the ancient Sanskrit language over W2XAF, July, 1935. (Author's Collection).  Robert E. Sherwood, director of the Office of War Information, dedicates WGEO’s new 100 kW transmitter in September, 1942. G.E. Engineer W. J. Purcell is at right. This unit replaced the first 100 kW transmitter that was shipped to KWID in San Francisco in December, 1941. (Author's Collection).  These were the updated wartime transmitters of WGEO (100 kW) and WGEA (50 kW) in June, 1943. (Museum of Innovation and Science, Schenectady)  Here is a territorial view of the G.E. transmitting plant at South Schenectady, July 1944. The white posts carried the transmission lines to the different antennas – most of which are out of view. (Museum of Innovation and Science, Schenectady)  This photo shows the WGEO transmitting plant in 1957. This was late in its life, when it served as a transmitting station for the Voice of America. Operations ceased here in 1963. (Author's Collection). |

|

General Electric Explores the Shortwaves:

In

the early years of

radio communications, it was believed that only the long waves (below

500 kHz) were

suitable for long distance communications. RCA,

the Navy, and other communications interests had

invested vast sums

of money to construct elaborate radio facilities for trans-oceanic

communications on the long waves. General

Electric, manufacturer of the prestigious and

massive Alexanderson

alternator, was a major recipient of these investment dollars, as well

as being

a major investor in the newly-formed company, RCA. General

Electric was

already developing transmitter technology through the facilities of its

medium

wave station, WGY, which began broadcasting in February of 1922 from

Building

36 at G.E.’s massive Schenectady factory complex. WGY

had a dual purpose – to provide programs

as an incentive for the public to buy G.E./RCA radio receivers, and to

serve as

a laboratory for the development of radio transmission technology. In

October of 1923,

G.E. installed an experimental shortwave transmitter on Van Slyck

Island, adjacent

to the G.E. plant in Schenectady, NY. The

10 kW transmitter operated on 105 meters (2,850 kHz), using the

experimental call

sign 2XI which had been acquired for other purposes in 1916. Its purpose was to investigate shortwave

propagation and coverage. The transmitted

audio was of little importance, so 2XI simply rebroadcast the programs

of WGY. Occasionally, the station was used

to relay

certain WGY programs to KGO in Oakland, California, G.E.’s newest

medium wave

station. As

mentioned, G.E.’s

engineers and scientists were also exploring the development of medium

wave

transmitters at WGY, but this experimental work was increasingly

interfering

with the regular broadcast activities of the station.

It was finally decided that a more ample experimentation

space was needed, and that it should be located some distance from the

industrial

electrical interference at the plant. For

this new "Radio Laboratory", a 58-acre plot was

acquired

at the corner of Mariaville Road and Burdeck Street in South

Schenectady/Rotterdam

Township, three miles west of the plant.

Construction

of the

facility took place during 1924/25. A

main 60x100 ft. brick building was built, which housed the power

equipment,

high voltage rectifiers, motor generators, a water-cooling system, and

the

audio amplifier and modulator equipment. There

were four smaller wood-frame buildings located on

the property,

housing individual transmitters for different projects.

Cooling water was piped from the main

building to each of these structures, and the modulator power was fed

to the

transmitters on overhead lines. There

were three 300 ft. steel towers, arranged in a triangular

configuration, which

allowed for the construction of many different types of antennas. There was also a fourth steel tower, 150 ft.

tall, and three wooden masts which supported a 109-meter wire antenna. The WGY transmitter and antenna were moved to

this location and were fed by program lines from the Building 36 studio. The 2XI operation at Slike Island was shut

down. The

main building contained

two transmitters– 2XAG was on 790 kHz with 20 kW, and it served as the

WGY

transmitter; 2XAH operated with 50 kW on 192 kHz long wave. Shortwave operations took place in the wooden

buildings – one on 109 meters (2,752 kHz), and another pair on 20 and

40

meters. They were given the experimental

licenses 2XAF and 2XAG. The purpose of these stations was to test

shortwave

propagation, antennas, and transmitter designs. After

experimenting with a variety of frequencies, it was

determined

that 31 meters was the best choice for daytime propagation, while 19

meters worked

best at night. This decision

foreshadowed the creation of these international broadcasting bands

which are still

in use today. As

with 2XI, WGY’s

program audio was used as the shortwave test signal.

These programs soon developed a following

from regions outside WGY’s normal coverage, and letters started coming

in from

around the world - particularly Europe and South America. Responding to this demand, the stations began

broadcasting on a regular schedule - 2XAF starting on February 10,

1924, and

2XAD on August 28, 1925. In 1927, these

call signs became W2XAF and W2XAD. (The

“X” in these call signs indicated they were licensed as “Experimental

Relay

Broadcast Stations”.) By

1930, regular

operation saw W2XAD operating at 15,480 kHz with 18 kW from 10:00 AM to

3:00 PM

Eastern Time, targeting Europe. Then W2XAF

broadcast to Latin America on 9,530 kHz using 25 kW from 4:00 PM to

midnight. The transmitter powers were

later raised to 25 kW and 40 kW, respectively.

As

shortwave receivers

became more common among amateur operators and listeners, the programs

and

schedules of G.E.’s two shortwave stations became increasingly

significant. This was no longer just a

grand experiment; it

had developed a sizeable audience around the world. Increasingly,

separate programs were being

produced for these shortwave audiences, featuring American music,

Broadway

shows, the Metropolitan Opera, baseball games, and bridge games. Much of this was aimed at American

expatriates living overseas rather than foreign cultures.

Virtually all programs were in English.

W2XAD

and W2XAF served

as an important communications link for the three expeditions of

Admiral

Richard Byrd to Antarctica (1928-30; 1934; and 1939-40).

A special directional antenna aimed at

“Little America” in Antarctica, designed by Ernst Alexanderson,

amplified the

station’s signal ten times in the direction of Byrd’s camp. Entertainment programs were transmitted to

the expedition crew every other Sunday night at 11:00 PM, sponsored by

major

newspapers around the country and repeated by NBC on 51 domestic

stations. Then, after the domestic

stations cut away,

the G.E. stations broadcast the “Byrd Mailbag”, reading letters sent by

friends

and family to the expedition crew, and averaging 75-100 letters a

night. 1 In

1935, a new station

slogan was adopted: “The Voice of Electricity”. The

stations’ signature ID sound was the

recorded crash of

a 10-million-volt

arc created in the G.E. laboratories, and it was broadcast at the

beginning and

end of each transmission. In

many parts of the

world, the two G.E. stations were the strongest signals coming out of

the

United States. By 1937, the program hours had increased –290 hours per

month for

W2XAF, and 220 hours for W2XAD. As the

notoriety of the stations increased, international goodwill and foreign

language programs became an important part of the G.E. stations’

schedules. NBC produced a series of

special programs

aimed at South America, broadcast over the stations in 1938. A weekday news program, called the “American

News Tower”, was inaugurated in June, 1937, consisting entirely of news

of the

United States as reported by the Press Radio Bureau. It

was designed specifically to counter the

false or distorted news being broadcast by the fascist stations in

Europe. A weekly “American Travelogue”

program was

also created, describing the most interesting tourist spots of the

country,

heard in English, French and Spanish.

Focus on South America: In

the late 1930’s, U.S.

government officials were becoming concerned about the increasing

amount of

propaganda coming out of the powerful German and Italian radio stations

and

directed at South America. Germany’s

eleven

100 kW transmitters practically dominated the shortwave bands in South

America. Their continuous propaganda in

Spanish and Portuguese was aimed at winning favor in South America, and

was

thick with anti-American and anti-British misinformation.

Of particular worry to officials was

Argentina with its decidedly pro-fascist military government. By contrast, the United States’ eleven

privately-owned stations were under-powered, under-funded, and mainly

repeated

domestic network programs in English totaling just 40 hours a week. A “Variety” article complained that the

American stations’ programs were “practically meaningless” to the South

American population. Charlie McCarthy,

Fred Allen, Abbott and Costello were cited as being wasted content for

non-English speaking listeners. Only a handful of programs were in

Spanish or

Portuguese. As

this attention to

South America increased, America’s international shortwave stations

came under

closer government scrutiny. Bills were

introduced in Congress to establish a government-owned station, but

they went

nowhere. Instead, in 1938, the

Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs was created, headed by Nelson

Rockefeller. Its purpose was to improve

the facilities and program content of the private international radio

broadcasters, as well as materials being generated by the motion

picture

studios. Financial grants were given to

the broadcasters to improve their transmission facilities.

Five new frequencies were authorized by the

FCC , and two of these were assigned to the G.E. stations.1

Pro-government news and commentary

material

was sent to the stations via teletype for their suggested use, although

they

were not permitted to identify the government as the source of the

material. In September, 1939, all

shortwave licenses were upgraded from experimental to commercial,

allowing the

stations to generate advertising revenue for the first time. With that change, all stations were given new

commercial call signs – W2XAF became WGEO, and W2XAD was now WGEA. A third General Electric shortwave station,

just

inaugurated in California, was changed from W6XBE to KGEI.

These

additional

investments resulted in many improvements at the American shortwave

stations,

especially after Pearl Harbor and America’s entry into World War II. By February, 1942, the eleven stations were

broadcasting 132 hours per day in 19 languages, and all were operating

with at

least 50 kW. In Schenectady, WGEO

installed a new 100 kW transmitter, nicknamed “Big Bertha” - the most

powerful

transmitter in the country at that time.2 Eight new curtain antennas, designed by Ernst

Alexanderson, were constructed for different bearings and frequencies,

focusing

the signals on their targets with 30-degree beams.

This antenna gain gave WGEO an effective

power of 1,200 kW aimed at South America. Newly-designed

audio peak limiters increased the stations’

average

modulation. Additional studio space in

the brand new WGY studio building allowed for more programs to be

produced for

shortwave audiences. By April, 1942, the

three G.E. shortwave stations – WGEO, WGEA, and KGEI – were

broadcasting 24-1/2

hours per day in fourteen languages. One

notable program, beginning in June of 1942, was called “Salute to the

Men in

Foreign Service”, heard on all three stations and aimed at American

servicemen

and embassy officials overseas. It was

also received and rebroadcast by Australian Broadcasting Company on

medium

wave.

The

ultimate solution

was implemented on November 1, 1942, when the government took control

of all

shortwave broadcasting in the United States. Essentially,

it leased the program time of all 14

transmitters belonging

to seven private companies on five-year cancellable contracts.4 These companies retained title to the

equipment and facilities, with their engineers continuing to man the

transmitters. All operating costs were

borne by the government, at no profit to the station owners. The newly-created Office of War Information

set

up studios in New York and San Francisco where it produced programs in

eleven

languages, supplemented by certain government-supervised programs

created by

NBC and CBS. . These were fed over

equalized phone lines to the various transmitter locations in what was

referred

to as the “Bronze Network”. The

programming staffs of all the shortwave stations were now O.W.I.

employees. This government operation

would eventually take the name of “The Voice of America”. At

WGEO and WGEA under

the OWI, broadcasting time nearly doubled. The old retired W2XED 25 kW

transmitter was updated and put back on the air as WGEX.

More rhombic and curtain antennas soon sprouted

on the G.E. grounds. Through

the course of

the war, the government invested large sums of money to increase the

country’s

shortwave broadcasting capacity. In

1943, it purchased 22 new RCA and G.E. transmitters which were placed

into

operation around the country. In 1944,

three new 200 kW transmitters were inaugurated at Crosley’s WLWO in

Bethany,

Ohio. That same year, CBS opened a

new

transmitter site in Delano, California, and NBC opened a facility in

Dixon,

California. By the end of the war, the

United States had the most formidable arsenal of shortwave transmitters

in the

world.

But

once the war was

over, this vast shortwave complex seemed to many in government to be an

anachronism. Much of the wartime

infrastructure was being dismantled as the country reverted to a

peacetime

economy, and there was considerable internal debate as to what should

be done

with the Voice of America. Ultimately, a

scaled-back operation was transferred to the State Department in 1945,

and this

small operation was reluctantly funded by Congress until 1948, when the

beginnings

of the Cold War and the Berlin Blockade made it clear that

international

broadcasting still had a future. Nonetheless,

the VOA was still nothing more

than a producer of programs, and the leasing of 36 private shortwave

transmitters continued as before. In

1953, Senator

Joseph McCarthy initiated congressional hearings to investigate the

claimed

existence of “subversives” at the VOA. While

ultimately proven to be unfounded, the negative

attention resulted

in a drastic reduction of its budget. Finally,

government leasing of a number of the private shortwave transmitters

ended on

June 27 of that year, and most of these stations were immediately shut

down by

their owners. The NBC and CBS transmitters

in Bethany, Dixon and Delano continued to operate, but its East Coast

transmitter sites were closed. In Schenectady, WGEA was discontinued

but WGEO

continued operations as a VOA relay station. 5 The

end for the

Schenectady stations finally came on November 1, 1963, when the VOA

took direct

control of the shortwave operations in Bethany, Dixon and Delano. That was also the year it opened its

sprawling new shortwave complex in Greenville, North Carolina. The Schenectady operation, with its tired old

transmitters, was no longer needed and was shut down.

The transmitter building was demolished and

some of the property eventually morphed into suburban neighborhoods. But one part of the facility continues in

operation today as the site of the WGY medium wave broadcast tower,

where it

has operated continuously since 1924.

This article originally appeared in the December, 2021, issue of The Spectrum Monitor For more WGEO/WGEA photos, see the WGEO

Photo Gallery

REFERENCES:

FOOTNOTES: 1

The Byrd camp also operated a shortwave

station in Antarctica, KRTK, which could be heard directly by shortwave

listeners. 2

In February, 1938, the FCC assigned these

five new “Pan American” shortwave frequencies to US stations. W2XAD and

W2XAF

received 9,550 and 21,500. W1XAL (later

WRUL)

in Boston was given 11,730 and 15,130. W2XE

Wayne NJ (CBS) continued its use of 6,120. The

frequencies had been set aside for use by

the U.S. at the 1932 Pan American conference in Montevideo, but had

been

reserved by the Navy and never been assigned to any station. They were finally assigned ahead of the next

World

Radio Conference in Cairo, where frequencies for the world’s shortwave

stations

would be set. The government was afraid

they would be given away to other countries at the Cairo conference if

not

activated. Nonetheless, the government

reserved the right to revoke the assignments if a government station

was ever

established. 3

Construction of this 100 kW transmitter

started in 1937, and it finally went on the air in July, 1939. It utilized a new 100 kW GE power tube that

featured a novel demountable filament. The

transmitter was frequency agile, meaning it could be used by either

station. It operated in Schenectady

until December of 1941, when it was purchased by the federal government

and

shipped to KWID in California to increase shortwave coverage in the

Pacific. The old W2XAD transmitter went

back into temporary service until G.E. could construct another 100 kW

transmitter, of similar design, which debuted in September, 1942. 4

The other stations in the government’s

shortwave wartime arsenal were: WLWO

Cincinnati; WRUL Boston; CBS’s WCBX on Long Island and WCAB in

Philadelphia;

NBC’s WNBC and WRCX in Bound brook NJ; Westinghouse’s WBOS in Boston

and WPIT in

Pittsburgh; and Associated Broadcasting’s KWID in San Francisco. All the stations voluntarily agreed to the

government’s takeover plan except for WRUL, which was ultimately seized

by the

government. 5

The only private owner that decided to stay

in the shortwave business was General Electric, who continued to

operate KGEI in

San Francisco as an international goodwill station.

In1960, the station was purchased by the Far

East Broadcasting Company (FEBC), which broadcast religious and

cultural

programs to Latin America and the Far East for the next 35 years. Finally, facing increasing costs and

declining listenership, FEBC closed KGEI in 1994.

|